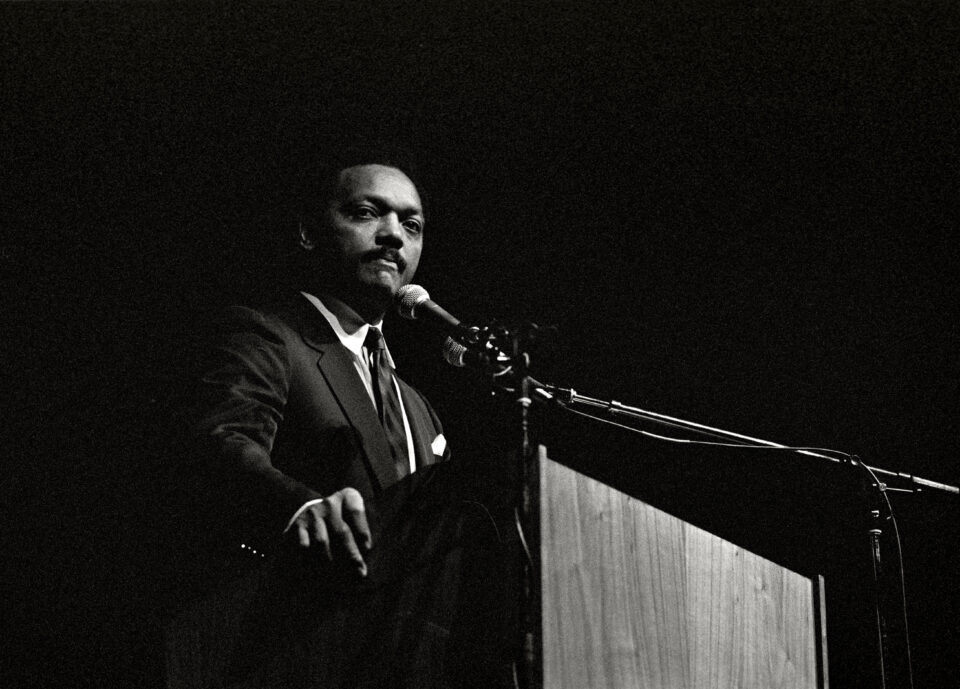

Rev. Jesse Jackson speaks to a Democratic gathering at the Cheyenne Civic Center on April 20, 1989, in Cheyenne, Wyoming. | Mark Junge/Getty Images

Rev. Jesse Jackson — a titanic civil rights leader, politician, and activist — died on Tuesday at the age of 84.

Over the course of a career that spanned decades, Jackson twice ran for president, in 1984 and 1988, though he later stepped back from electoral politics.

To get a better sense of Jackson’s legacy and his influence on the Democratic Party, I reached out to Osita Nwanevu, a contributing editor at the New Republic who has spent time thinking and writing about Jackson.

Our conversation, edited for length and clarity, is below.

Key takeaways

Jackson was a serious contender for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1988, and his Rainbow Coalition mobilized a broad set of groups he believed had an interest in progressive policy.

Jackson remained influential after stepping back from electoral politics but would later recede from public memory and the public eye.

His vision and his ability to unify forward-looking social and economic agendas provides a potential model for today’s Democratic Party, exemplified by politicians like New York City Mayor Zohran Mamdani.

Who is Jesse Jackson? How did he transition from activism to electoral politics in 1984 and 1988?

Jackson is part of the King-era civil rights movement. He’s instrumental in all of that. As the civil rights movement develops in the 1970s, people go in all kinds of different directions. You have people who take the Black Power movement and say, “We’re going to develop Black capitalism, develop business interests, and develop our own kind of economic power.” You have people continue on the social justice route. You have people who are getting into politics. There are all these divergent strands, and Jackson sits at the center of all of them while still being a very prominent public voice in the movement as a whole.

I think Black Americans develop enough of a political constituency that not only do they come to matter more and more in the political realignments that are going on in the 1970s, but it becomes plausible, at least to some people, that they could mount a viable presidential campaign.

And that’s what Jackson does. He’s extraordinarily charismatic; I think one of the best orators of the century. He launched a campaign in ’84 that gathered a lot of attention but doesn’t really go anywhere. ’88 is different. There is a stretch of several months where it looks entirely plausible that Jackson can be the Democratic nominee in ’88. That’s been my interest in him as a figure. I spent some time with him a few years ago in advance of the 2020 Democratic primary for a profile that was ultimately killed, but I wanted to talk with him about the things the party was confronting as somebody who had been the center of a lot of the same debates.

One of the core elements of his presidential campaigns was the Rainbow Coalition. Can you describe what that was?

The Rainbow Coalition was basically intended to be an amalgam of all the different groups that he saw as having an interest in progressive policy: not just African Americans, but Latinos, LGBT people, poor people in general, the unhoused, everybody that he thought could have a stake in a more progressive political agenda. He tried to knit them together.

And I think that one of the things that was most important about his 1988 campaign, as opposed to the ’84 campaign, is that, in ’88, he really stakes a lot on trying to include and, in fact, to put white working-class voters at the center of that agenda, as well. I think that’s part of why he attracts the attention he does the second time around. He wins this very surprising victory in Michigan.

[In] the debates we’re having now — and have been having for some time — in the Democratic Party about whether we push forward on racial justice or do economic populism that’s more capacious and also peaks to the concerns of where people have been interested in Donald Trump, Jackson basically says, in ’88, we’re going to do all of these things at once with a really forward-looking social agenda and economic agenda that comes to speak to all the constituencies that are downtrodden and marginalized in America.

Unfortunately, it’s a presidential campaign that doesn’t really succeed. I’ve been interested in thinking through why that wasn’t the case in ’88 and whether it could be the case now, but that was the underlying idea.

He doesn’t succeed. He does have this incredible speech at the ’88 convention, and then he steps back from electoral politics, right?

He does. He’s still a major political figure. The Rainbow Coalition puts him in a place where he becomes a touchstone for different parts of the Democratic coalition. He’s seen as somebody you speak to if you want to demonstrate that you’re interested in questions of poverty and questions of racial justice. He hosts events, he hosts town halls — these kinds of things.

He’s in the political arena, but not as much of a major figure as he initially had been. Through the ’90s, especially, I think people like Bill Clinton and others had their careers and their time in politics shaped substantially by their interactions with Jackson.

Two decades later, Barack Obama runs and wins. What does their relationship look like?

There’s this infamous moment where Jackson was caught off-mic during the 2008 Democratic primary. And I think that there’s this perception publicly that there was some tension and some friction. He critiqued the Democratic Party. He critiqued Barack Obama from the left on many occasions.

In the last couple of decades, as best as I can tell, he is focused on building out the Rainbow Coalition as an organization, and there’s a lot of work in and around Chicago especially. But, you know, you’ll see him participate in other protest movements over the last couple of decades as well. He’s not as much of a kingmaker or behind-the-scenes operative in the 2000s and 2010s as he once had been but certainly a respected figure — and one that matters symbolically to a lot of people.

What do you think Jackson’s legacy will look like?

It’s hard to say, because I think that he receded from the public memory a lot in these last four decades. And this is somebody who was once one of the most famous people in the world.

As we continue to confront some of the basic questions of Democratic politics — the place of social justice issues versus economic issues — as we continue to have those debates, I think we’re going to have to turn to Jackson’s career as instructive. I think it will matter more and more to people that he ran campaigns that sat at the center of some of the tensions that we are relitigating now. I hope that people learn from him and his work there.

I also think he’s at this point deeply underrated as a rhetorician, as an orator, as a speaker, as somebody who could galvanize the public. There was nobody like him while he was active in political life, and maybe that’s something that gets resurrected in the public memory, as well.

How are you going to remember him?

I’m going to remember him as one of the most important figures in the 20th century, and somebody who, I think, emerges as a public figure in this moment where nobody is really sure what the civil rights movement should turn into.

I think that his life tells us a lot about the different tensions and the complexities of trying to advance racial justice in this country. It’s not a straight line. It’s not this cliche that we have about the arc of history bending towards justice. It might, but there are a lot of kinks in that arc. You can find a lot of them in Jackson’s career.

He was an extraordinary person, and I wonder now, as people remember him, if some of that legacy is brought to the fore.

Jackson practiced a sort of a politics of the possible with his Rainbow Coalition, envisioning a better version of what politics could achieve. Do you think we’re going to see that going forward in the party?

I certainly hope so. I think that Zohran Mamdani, even more so than Bernie Sanders, really does seem like an heir to the coalition and the kind of politics that Jackson represented — not just as a matter of substance, but as a matter of political style — his kind of warmth, openness, and trying to connect directly to people.

People really felt a personal connection to Jesse Jackson in a way that I think might be unrivaled. People felt that they knew him or wanted to relate to him in a kind of parasocial way. I think that that kind of politics has a future in the Democratic Party.

I think the questions for progressives are: Why haven’t we made the gains that we have hoped for in places outside of New York City? Why isn’t the Rainbow Coalition a majority coalition yet, despite the efforts of people like Jackson and all those who follow his example?

I think there may be lessons to learn from his runs. For me, personally, I do think that Jackson politics are the right politics for the party. He’s somebody who offers that vision, and it’s precisely the time where centrists are beginning to take over the party and shape its direction. He’s one of the first people on the front lines of this battle that we are fighting now, that we take for granted now.